Last week, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service confirmed that a litter of five endangered red wolf pups died in North Carolina after they were left to fend for themselves when a vehicle struck and killed their father in June.

This represents a major setback in the reintroduction effort for red wolves, of which just around 20 remain in the wild. But data shows the tragedy is not altogether surprising: Car collisions are among the leading causes of death for this struggling species—and many others like it.

The situation has sparked a renewed push from conservationists for the government to install grassy bridges known as wildlife crossings over U.S. Highway 64 in this region so wolves and dozens of other species can pass through the area without dodging cars, trucks and motorcycles. These efforts are part of a broader strategy to develop a wildlife crossing network in some of the top wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots across the U.S., largely funded by a $350 million grant program included in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

But there could be a climate-related wrinkle in these plans. A growing body of research shows that many species are changing their migratory patterns or moving to entirely new habitats over time to escape warming temperatures and climate extremes.

Wildlife crossings could be crucial to helping animals survive these widespread migrations on road-dominated landscapes—but only if we can predict the right places to put them, experts say.

The Road to Extinction: Each year, there are an estimated 1 to 2 million collisions between motor vehicles and large animals in the U.S. Roughly 200 people die. Estimates suggest that crashes in the country also kill around a million vertebrate animals—per day.

“I think it’s probably a vast underestimate,” environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb told Vox. He recently authored the book Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, which outlines the extent to which roads have decimated wildlife populations. “I think that’s one of the tragic ironies of automobility, that speed is both the destroyer of wild animals and it also blinds us to that destruction.”

For animals that stay away from the asphalt, roads can still have cascading impacts on the individual or population health of a species. The largest concern is that roads often cut directly through a species’ habitat, which can disrupt migration, degrade key resources such as water and food, or reduce genetic diversity if part of the population is stuck on the other side.

“The precise reason for us being able to get from point A to point B so efficiently is the inverse for wildlife,” Matt Skroch, a U.S. conservation project director at Pew Charitable Trusts, told me. “Those roads and highways are often barriers.”

The good news? He says there is a solution “staring us in the face”: wildlife crossings. The term is a catchall for structures that can allow animals to traverse human-made barriers safely, but they can come in a variety of forms—from the grassy overpass that enables pronghorn to run across Wyoming’s Highway 191 to the long underpass that allows tigers to scamper beneath National Highway 44 in India.

In the U.S., there are currently more than 1,000 wildlife crossings and counting, largely thanks to a recent influx of federal, private and philanthropic funds. So far, data shows they are highly effective; one study found that crossings on Highway 9 through the Blue River Valley in Colorado reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions by nearly 90 percent. These structures can be expensive to build, costing between $500,000 and $6 million, but recent research suggests that the money saved by avoiding crashes recoups the costs in just a few years, along with potentially saving lives.

However, the location of these crossings are largely focused on where animals are currently traversing—something that could change as the climate crisis accelerates.

Animals on the Move: Models suggest that human-caused climate change is fueling a worldwide redistribution of wildlife, from massive Asian elephants to tiny wood frogs.

Scientists are working on refined models for individual species, but general trends suggest that tropic species are moving northward as winters warm, while some species are seeking refuge from the heat at higher elevations. Wild animals are also sometimes pushed to new areas during acute climate-related events, such as wildfires or droughts.

In 2023, a group of experts from the government, universities and nonprofits—including Skroch from Pew—authored a report urging policymakers to take this potential climate-fueled reshuffling into account when siting and funding new wildlife crossings.

“We know that this climate is going to be different,” Skroch said. “Will those structures still work in the way that they’re intended to work today? That is a legitimate question mark.”

Currently, federal funding for crossings is largely distributed based on areas with the highest number of wildlife-vehicle collisions, which is crucial for addressing public safety and conservation risks. But the authors stress that agencies should require future wildlife crossing proposals to incorporate a longer-term climate change metric into their overall plans, and that increased research and Indigenous knowledge can help inform this.

Some experts say that part of the solution could be developing adaptable wildlife crossings, which could potentially be changed or moved to follow the wildlife to new areas. Crossings are often built with concrete or steel, which can be costly and heavy. A 2020 study found that lighter materials such as fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs) can be less expensive and potentially easier to use during construction of the structures in certain cases.

“We need something that’s light, that you can just drop in, and then you can pull it out and move it if the circumstances change,” study co-author Robert Ament, a retired professor who formerly led the Road Ecology Program at Montana State University, told me. He is currently a member of the nonprofit International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Connectivity Conservation Specialist Group, where he helps countries around the world develop their own wildlife crossings tailored to specific animals—from Asian elephants in India to orangutans in Indonesia.

As an example of a lightweight structure, Ament pointed to an overpass on the N-225 highway in the Netherlands made using FRP, which is water- and corrosion-resistant. Engineers are currently working on other designs that focus on materials that can be stacked, which would make it easier to assemble or disassemble, according to a 2021 report from the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“If we’re going to allow animals to adapt under climate change, we really have to maintain landscape integrity so that they can move about, move up in elevation, move north or south, [or] towards the poles, depending on the pressures that they’re facing,” Ament said.

More Top Climate News

Thousands of government leaders, business representatives, nonprofit heads and guests have descended across New York City for Climate Week. President Joe Biden is set to speak today at the Bloomberg Global Business forum, where he is expected to tout his administration’s clean energy wins. However, Politico’s Zack Colman and Sara Schonhardt write that the “the specter of Donald Trump’s potential return to the White House” looms over the event as world leaders and environmental advocates express concerns over the potential rollbacks of climate policies he could enact if he wins the upcoming election. You can find the full Climate Week agenda here.

Meanwhile, Dutch nonprofit True Price is working to uncover the environmental toll of food production around the world through a new accounting approach, Lydia DePillis, Manuela Andreoni and Catrin Einhorn report for The New York Times. Agriculture is one of the leading causes of global habitat loss, causing species extinctions, groundwater depletion and pollution. Farming is also responsible for around 10 percent of U.S. emissions. Through an approach called “true cost accounting,” economists are working to assign dollar values to these environmental damages to increase awareness among consumers.

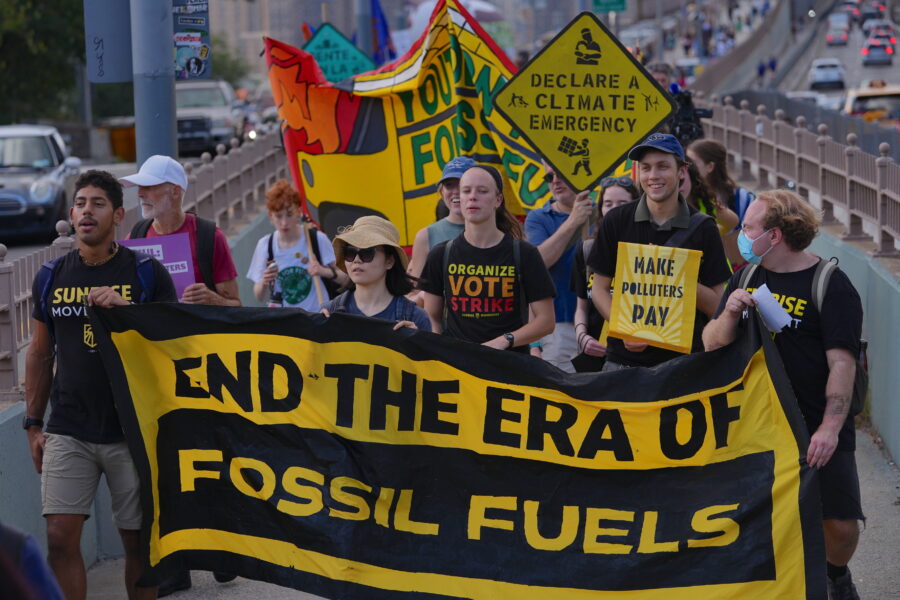

On Monday, climate activists from the Sunrise Movement protested outside Vice President Kamala Harris’ home in California. To stress the need for action to prevent climate extremes, the protesters brought scorched couch cushions from a house that burned in the Airport fire that recently ravaged communities along the Santa Ana Mountainside. Later on Monday, Harris said on social media site X that if elected, she will “tackle the climate crisis with bold action to build a clean energy economy, advance environmental justice, and increase resilience to climate disasters.”

In the U.S., there is an increased focus on insurance commissioner races as climate-fueled extreme weather ramps up premiums, Jesse Nichols reports for Grist. Only 11 states elect, rather than appoint, their commissioner, and those races have garnered more attention from voters in recent years—but some experts are worried that potential efforts to appeal to voters could downplay potential risks for the market.

“It’s very fraught to have an elected official in charge of regulating this market,” Ben Keys, an economist and professor of real estate and finance at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, told Grist. “If you set prices too low, then you make voters happy—but at the cost of not reflecting the true risk. That’s going to encourage people to build more in risky areas.”

Forecasters warn that a tropical storm in the Atlantic could soon strengthen into a hurricane that is set to arrive in Florida by Wednesday. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis issued a state of emergency ahead of the potential onslaught.

“There is a significant threat of storm surge, coastal flooding and erosion, heavy rainfall and flash flooding, and damaging winds to the Florida Gulf Coast,” the order says.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,